False Starts: Pick Up the Phone

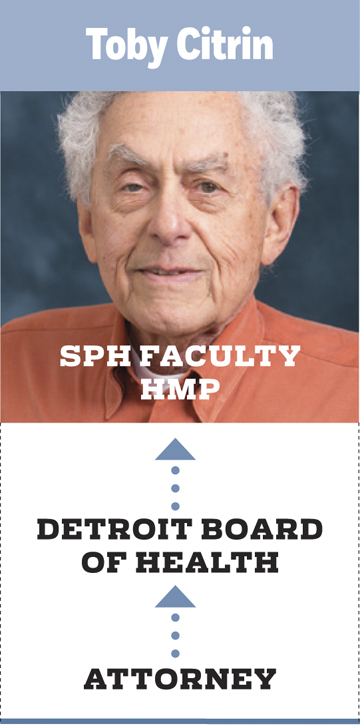

In 1970 lawyer Toby Citrin was contentedly working in a family business when his phone

rang one Sunday afternoon. It was Roman Gribbs, Detroit's newly elected mayor, and

he was calling, at the recommendation of a mutual friend, to see if Citrin would serve

on the Detroit Board of Health.

In 1970 lawyer Toby Citrin was contentedly working in a family business when his phone

rang one Sunday afternoon. It was Roman Gribbs, Detroit's newly elected mayor, and

he was calling, at the recommendation of a mutual friend, to see if Citrin would serve

on the Detroit Board of Health.

"I don't really know anything about public health," Citrin said.

The next thing he knew, Gribbs had put the city's health commissioner, George Pickett, on the line. It'll only take three to four hours every month, Pickett assured Citrin. You'll have to attend a monthly meeting and read background material, but that's all.

OK, Citrin said.

At his first board meeting, the mayor's liaison took Citrin aside and informed him that, according to the city charter, because he'd been appointed to serve out the term of a recently deceased senior member, Citrin was now president of the board.

At the time, Citrin recalls, the health board was so powerful it ran two Detroit hospitals. Shortly after Citrin became board president, one of those two, a hospital specializing in tuberculosis, made headlines when the media reported on alleged drug and prostitution rings operating inside the facility. Citrin found himself in a media storm.

But he fell in love with public health. Early in his tenure, he launched an initiative for board members to accompany public health nurses on their daily rounds. The experience showed Citrin the complexity of the determinants of health, and he was hooked. Soon he was asked to join other boards and task forces and to chair a commission charged with writing Michigan's first public health code. A faculty appointment at SPH followed in 1980.

"When students occasionally ask how they can get to do what I do," he says today, after 46 years in the field, "I smile and say they have to make sure they answer the phone on Sundays."